Jonathan Pugh is Reader in Island Studies, Newcastle University, UK. He has over 70 publications and is noted for his work on the ‘relational’ and ‘archipelagic’ turns in island studies, disrupting the figure of the insular island. Jonathan has held fellowships, given many international keynotes and invited lectures, including at Princeton, Harvard, Virginia Tech, London, Cornell, Vienna, Zurich, Trinity College Dublin, Rutgers, California, University of West Indies and National Taiwan Normal University. Jonathan’s recent work – Anthropocene Islands: Entangled Worlds (Pugh and Chandler, 2021) – examines how islands play an increasingly prominent role in Anthropocene critical thinking, knowledge and policy practices. Jonathan.Pugh@ncl.ac.uk.

Categoria: Authors-en

The Island in Northern-American and English 20th and 21st – centuries Paranormal Horror Films and TV-Shows

[In Cinema, Horror]: Although prolific in representations in horror cinema and television shows, the island as an object of horror has yet to be further studied. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the island has been the stage for numerous horror films and television shows. Notably, the island is generally represented as the stage for horror, very rarely being the source of horror itself. However, there are some notable examples where the island itself represents the horror whether because of its inhabitants, for example in Doomwatch (Sasdy 1972) or The Wicker Man (Hardy 1973), or due to its fauna and flora, like Jaws (Spielberg 1975), and The Bay (Levinson 2012). The characteristics that the island evokes can be read in a binary. Instead of representing a private paradise, these islands usually represent individual (or group) seclusion that brings about the need for survival. The island often functions as the representation of exclusion from ‘normal’ society and the characters’ inability to reach it safely, often connecting it to the idea of the supernatural, such as in Blood Beach (Bloom 1981), The Woman in Black (Watkins 2012), an adaptation of Susan Hill’s homonymous work (1983), and Sweetheart (Dillard 2019), or of madness, for example in Shutter Island (Scorsese 2010) or The Lighthouse (Eggers 2019). It also evokes the feelings of imprisonment, limited resources, strange or foreign life forms, and a place where privacy can mean the concealment of horror to outsiders, such as Midnight Mass (Flanagan 2021), which evokes religious horror that is kept at bay from the rest of the world and contained because it is set on an island, or Fantasy Island (Wadlow 2020), where the notion of paradisiac and idyllic islands is subverted into its dystopic opposite. The island in horror films has been studied from a postcolonial perspective (Williams 1983; Martens 2021), particularly concerning films of Northern-American or British production that set the horror on foreign islands, namely those which are not European and white-centred, focusing, for instance, on the representation of African-Caribbean religions and practices and the zombie figure. It has also been studied through the lens of diabolical isolation and as the site for scientific experiment, like The Island of Lost Souls (Kenton 1934), the adaptation of H. G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Mureau (1896), creation and/or concealment, as in Sedgwick’s study about ‘Nazi Islands’ (2018). However, it is from Australia that the study of the island as a horror site seems to be more fertile, specifically studies of ‘Ozploitation’, that is, films that explore the Australian island landscape as a product of colonisation and of disconnection from the (main)land (Simpson 2010; Culley 2020; Ryan and Ellison 2020).

Bibliography:

CULLEY, NINA. “The Isolation at the Heart of Australian Horror.” Kill Your Darlings, Jul-Dec 2020, 2020, pp. 263-265. Informit, search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.630726095716522.

MARTENS, EMIEL. “The 1930s Horror Adventure Film on Location in Jamaica: ‘Jungle Gods’, ‘Voodoo Drums’ and ‘Mumbo Jumbo’ in the ‘Secret Places of Paradise Island’. Humanities, vol. 10, no. 2, 2021, doi: 10.3390/h10020062.

RYAN, MARK DAVID, AND ELISABETH WILSON. “Beaches in Australian Horror Films: Sites of Fear and Retreat.” Writing the Australian Beach. Local Site, Global Idea, edited by Elisabeth Ellison and Donna Lee Brien. 2020. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

SEDGWICK, LAURA. “Islands Of Horror: Nazi Mad Science and The Occult in Shock Waves (1977), Hellboy (2004), And The Devil’s Rock (2011).” Post Script, special issue on Islands and Film, vol. 37, no. 2/3, 2018, pp. 27-39. Proquest, www.proquest.com/openview/00ccdba578653d3fe1a5b2e7b5bfb0b5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=44598. Accessed January 27, 2022.

SIMPSON, CATHERINE. “Australian eco-horror and Gaia’s revenge: animals, eco-nationalism and the ‘new nature’.” Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 4, no. 1, 2010, pp. 43-54, doi: 10.1386/sac.4.1.43_1.

WILLIAMS, TONY. “White Zombie. Haitian Horror.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, vol. 28, 1983, pp. 18-20. Jump Cut, www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC28folder/WhiteZombie.html. Accessed January 27, 2022.

Filmography:

Blood Beach. Directed by Jeffrey Bloom, The Jerry Gross Organization, 1981.

Doomwatch. Directed by Peter Sasdy, BBC, 1972.

Fantasy Island. Directed by Jeff Wadlow, Columbia Pictures, 2020.

Jaws. Directed by Steven Spielberg, Universal Studies, 1975.

Midnight Mass. Directed by Mike Flanagan, Netflix, 2021.

Shutter Island. Directed by Martin Scorsese, Paramount Pictures, 2010.

Sweetheart. Directed by Justin Dillard, Blumhouse Productions, 2019.

The Bay. Directed by Barry Levinson, Baltimore Pictures, 2012.

The Island of Lost Souls. Directed by Erle C. Kenton, Paramount Pictures, 1932.

The Lighthouse. Directed by Max Eggers, A24, 2019.

The Woman in Black. Directed by James Watkins, Hammer Film Productions, 2012.

Wicker Man. Directed by Robin Hardy, British Lion Films, 1973.

Further Reading

CHIBNALL, STEVE, AND JULIAN PETLEY (eds.). British Horror Cinema. British Popular Cinema. 2002. London and New York: Routledge.

HUTCHINGS, PETER. Hammer and Beyond: The British Horror Film. 1993. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

—. Historical Dictionary of Horror Cinema, 2nd edition. 2018. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

—. The A to Z of Horror Cinema. 2009. Lanham, Toronto, Plymouth: The Scarecrow Press.

LEEDER, MURRAY. Horror Film. A Critical Introduction. 2018. New York, London, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury.

SMITH, GARY A. Uneasy Dreams: The Golden Age of British Horror Films, 1956-1976. 2000. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company.

WALLER, GREGORY A. (ed.). American Horrors. Essays on the Modern American Horror Film. 1987. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Paulo César Vieira Figueira

Paulo Figueira has a PhD in Atlantic Islands – specialization in Cultural Heritage (Ilhas Atlânticas: História, Património Cultural e Quadro Jurídico-Institucional – especialidade em Património Cultural). He is an integrated member of CEComp and a collaborating member of CLEPUL. Since graduation, he has shown interest in the insular character of Madeiran identity, through literature (poetry and historical novel) and with relevance to the works of José Agostinho Baptista and João dos Reis Gomes, on which he has presented several communications and articles. In the same way, he has sought to study Cape Verdean and Azorean writers. paulocv@sapo.pt.

Viagens, de João dos Reis Gomes

Viagens appears in the travel literature of Madeiran authors as the posthumous compilation of three works by João dos Reis Gomes, Através da França, Suíça e Itália, Três Capitais de Espanha and Através da Alemanha. The particularity of this work is that could be understood as an exemplar of travel literature by a Madeiran author about trips made outside the insular space or the portuguese space.

We believe that this type of travel literature produced by authors from Madeira who travel to continental spaces allows, in the case of João dos Reis Gomes, the opening of another research suggestion that is the vision of the European continental space by an islander from a territory of the current European outermost region. The texts by João dos Reis Gomes also suggest the interpretation of the tourist phenomenon at the beginning of the 20th century, linked to religious, leisure or medicinal and therapeutic reasons, something also experienced in the insular space.

In this context, the testimony of an islander’s journey in a continental space reveals a measure of description characteristic of someone that lives on an island and could measure the world through it, which allows us to envision insularity as an opening to the world.

In Viagens, João dos Reis Gomes, motivated by the knowledge of the other, offers the reader the perspective of the traveling writer and not a simple tourist commentary: “apodera-se do ritmo e da técnica do episódio e do relato histórico, assegurando a cor local, através de um olhar testemunha, subjetivo. Surge, então, a categoria do escritor viajante, com uma dupla função: ser um olhar que escreve e, ao mesmo tempo, um escritor” (Mello, 2010: 145). Regarding the three books that make up the volume Viagens, we talk about an experience resulting from the second Madeiran pilgrimage to European Marian shrines, a leisure trip to Spain and a trip for health and leisure reasons to Germany.

Através da França, Suíça e Itália was published as a book in 1929, based on the chronicles of João dos Reis Gomes first published in the Diário da Madeira, in 1926, the year of the second Madeiran pilgrimage. We think that the second Madeiran pilgrimage is part of the context of the great transnational pilgrimages that take place all over Europe, influenced by the climate of the apparitions of Fátima, of the canonization of Margaret Mary Alacoque, on May 13, 1920, by Pope Benedict XV, and by the large number of pilgrims to the Lourdes cave, a phenomenon of faith, facilitated by Catholic groups.

However, we are talking about a story that is a non religious testimony, because João dos Reis Gomes confesses that he does not feel able to address religious matters and writes because his friends asked him to do so: “Tinham-me alguns amigos pedido, com penhorante insistência, que lhes desse umas breves impressões desta peregrinação” (Reis Gomes, 2020: 23). We believe that one of the main points of interest of this travel testimony is the demonstration of the author’s conservative thinking and the reflections on politics, society and culture, taking into account that João dos Reis Gomes is a military man and an islander who is faced with different ways of being. We can also add a certain admiration for the Italian political order, especially if we are confronted with the events in Portugal and the precarious situation of the First Republic: “O viajante sente a perfeita comunhão do povo com o salvador da Itália [Mussolini]” (Reis Gomes, 2020: 157).

As an island traveler, nostalgia takes hold during some episodes of the author and his entourage, as is the case of the comparison with the Côte d’Azur and the mountains of Switzerland: “O espetáculo [the swiss landscape] é, na verdade, grandioso e comovedoramente evocativo. Ninguém deixou de pensar, mais vivamente, na sua casinha da alterosa ilha” (Reis Gomes, 2020: 195).

Três Capitais de Espanha is the report of a private trip, dedicated to the son of João dos Reis Gomes, Álvaro Reis Gomes, “companheiro nestas digressões” (Reis Gomes, 2020: 227). The journey of the traveling writer is intertwined with Spanish history, from the North, Burgos, through Toledo, conquered by Alfonso VI, to the imperial city of Seville. The traveling writer’s testimony is based on art and culture and the subjectivity of admiration: “Mas, porque escrevo, então?! Primeiro, por uma imposição de espírito ou, melhor, de sensibilidade, que me não deixa conter as emoções colhidas – […]; segundo, porque, dado o direito de admirar, na apreciação de qualquer facto, país ou obra de arte, há sempre um certo fator subjetivo” (Reis Gomes, 2020: 229).

Através da Alemanha is a book of 1949, based on the chronicles first published in Diário da Madeira, in 1931. The purpose of the book edition is to witness to the reader the German civilization before the Second World War: “apenas elementos para um confronto entre o passado [1931] e o presente [1949]; confronto que, por tão desolador como expressivo, oxalá pudesse contribuir – ingénua utopia! – para adoçar a alma e prevenir a consciência” (Reis Gomes, 2020: 283).

In addition to approaching a country far from the European periphery, João dos Reis Gomes’ interests lie in Neubabelsberg, the visit to the UFA studio (Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft) and the contemplation of cinematographic art, the ascent of the Rhine (where he found inspiration to his book A Lenda de Loreley, contada por um latino) and the emotion, as journalist and writer, in the visit of Gutenberg’s museum, in Mainz.

For all these reasons, we believe that Viagens is an example of the island traveler writer and the outside perspective he adds to the island world, due to the awareness that these are different worlds. The themes discussed reflect that insularity is part of a global world, in which events that occur in a given space and time are interconnected and act on several other geographic points, whether of a political, cultural, philosophical or scientific nature.

References

Collot, Michel (2014). Pour une Géographie Littéraire. Paris: Éditions Corti.

Cristóvão, Fernando (2002). Condicionantes Culturais da Literatura de Viagens. Coimbra: Almedina.

Mello, Maria Elizabeth Chaves de (2010). O relato de viagem – narradores, entre a memória, o fictício e o imaginário. In Dalva Calvão e Norimar Júdice (Org.). Gragoatá, 28. Niterói: Universidade Federal Fluminense. 141-152.

Nucera, Domenico (2002). Los viajes y la literatura. In Armando Gnisci (Org.). Introducción a la Literatura Comparada. Barcelona: Editorial Crítica. 241-290.

Pita, Gabriel de Jesus (1985). Decadência e queda da Primeira República analisada na Imprensa Madeirense da época. In António Loja (Dir.). Atlântico, 3. Funchal: Eurolitho. 194-209.

Reis Gomes, João dos (1949). Através da Alemanha. Lisboa: Livraria Clássica.

Reis Gomes, João dos (1929). Através da França, Suíça e Itália. Lisboa: Livraria Clássica.

Reis Gomes, João dos (1931). Três Capitais de Espanha: Burgos-Toledo-Sevilha. Funchal: Diário da Madeira.

Reis Gomes, João dos (2020). Viagens. Funchal: Imprensa Académica.

Historical Novels – João dos Reis Gomes

The historical novels of João dos Reis Gomes correspond to three titles, A filha de Tristão das Damas (1909 and 1946), O anel do Imperador (1934) and O cavaleiro de Santa Catarina (1942), which focus on political, historical and cultural issues and local traditions. From the point of view of literary technique, these are not innovative novels, clearly influenced by the structure of the romantic historical novel model.

The relationship of these works by João dos Reis Gomes with insularity, specifically with the construction of Madeiran identity, takes place in a perspective in which regionalism and the affirmation of regions begins to be a reality in Europe.

Born in France, in the mid-19th century, regionalism influenced the struggle for emancipation in many regions, including Madeira (Vieira, 2001: 144). The Madeiran intellectual elite sought to legitimize the struggle for greater visibility of the archipelago, through the recovery of historical references, traditions and folkloric traits that supported this insular identity: “Tão pouco uma classe política, alheada ou desconhecedora do passado histórico terá possibilidades de fazer passar e vingar o seu discurso político” (Vieira, 2001: 143).

The insular identity difference starts to be built by the generations of the beginning of the 20th century, emphasizing History, other sciences and Literature: “estas gerações, com evidentes influências regionalistas, procuraram, através da história, da literatura, da ciência, a construção e validação de um panteão regional sobre o qual assentasse uma marca de diferença” (Figueira, 2021: 130)[1].

It is in this context that A filha de Tristão das Damas is published, in 1909. The first self-styled Madeiran historical novel has as its central point the help of the third donee of Funchal, Simão Gonçalves da Câmara, in the conquest of Safim, by Portugal. This motive serves to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Madeira’s intervention, as one of the archipelago’s historical episodes, as well as to present a subtle critique of the administrative autonomy of 1901. The publicity of Portuguese foreign policy’s commitment to the maintenance of the African Empire is also relevant. In fact, in 1946, the date of the second edition of the work, in addition to the regionalist aspect, it is again the assumption of Portugal as a colonial power, outside the sphere of emerging powers (USA and USSR), that guides the publication of this historical novel. In 1962, the novel is published again, but in fascicles by the Diário de Notícias do Funchal, with the aim of defending the Guerra do Ultramar (Overseas War) and the legitimation of the Portuguese Empire.

O anel do Imperador tells the story of Napoleon’s passage through Funchal, during his second exile, this time to the island of Saint Helena. The question of this historical episode allied to the fictional visit of Miss Isabel de S. to the French Emperor created a popular tradition fixed in the novel by João dos Reis Gomes. Behind the fiction there is, however, the propaganda of the figure of Salazar, similar to the episode of Napoleon in Madeira, seeking to present the figure of a sensitive political leader who deserves the acceptance of his Madeiran peers. It should be remembered that, in the 1930s, between the government of the military and the definitive rise of the Estado Novo, the episode of Revolta da Madeira, a political-military insurrection against the government of the military dictatorship, deepened the atmosphere between Madeira and the capital, in addition to the monopoly laws in relation to flour and milk, at the time, important industries in the archipelago.

Salazarism, in its propaganda action, sought to welcome the Madeiran elites into its midst, in a climate of harmony between the archipelago and the Government, in which the regionalist slope was exponentiated according to the homeland.

O cavaleiro de Santa Catarina offers the reader an account of the life and legend of Henrique Alemão, “sesmeiro da Madalena do Mar”, whose identity is believed to be that of Ladislaus III, the Polish king who disappeared in the Battle of Varna (1444).

The author, with this book, in addition to the attempt to preserve a heritage buffeted by the 1939 alluvium in Madalena do Mar, seeks to explore the myth of sebastianism, as there is a clear identification between the life of the Polish king and that of D. Sebastião, because both try to fight the Mohammedans, but end up missing in the decisive battle, the Polish king in Varna and the Portuguese king in Alcácer Quibir.

The circumstances of this historical novel, the 1939 alluvium and the myth of D. Sebastião, are also related to the exhibition of the Portuguese World in 1940 and the celebration of Portuguese double independence (1140 and 1640). Once again, João dos Reis Gomes appropriates a pantheistic figure from Madeira’s history and tradition to serve regionalist intentions and, at the same time, the homeland, which, in a difficult political period, in the middle of the Second World War, seeks to maintain the shaky neutrality in relation to the blocs of the belligerent powers. The sebastic figure of Henrique Alemão, in this context, invokes, in our view, the soul of national resistance and Portuguese courage in a difficult juncture.

References

Figueira, Paulo (2021). João dos Reis Gomes: contributo literário para a divulgação da História da Madeira [Phd thesis]. Funchal: Universidade da Madeira.

Figueira, Paulo (2019). O romance histórico na Madeira: o caso de A filha de Tristão das Damas, de João dos Reis Gomes. In Sérgio Guimarães de Sousa e Ana Ribeiro (orgs.). Romance histórico: cânone e periferias. Vila Nova de Famalicão: Húmus/Centro de Estudos Humanísticos da Universidade do Minho.

Marinho, Maria de Fátima (1999). O romance histórico em Portugal. Porto: Campo de Letras.

Rodrigues, Paulo (2012). O Anel do Imperador (1934), de João dos Reis Gomes, entre a História e a Ficção: Napoleão e a Madeira. In Maria Hermínia Amado Laurel (dir.). Carnets, Invasions & Évasions. La France et nous, nous et la France. Lisboa: APEF/FCT, 81-97.

Vieira, Alberto (2001). A Autonomia na História da Madeira – Questões e Equívocos. In Autonomia e História das Ilhas – Seminário Internacional. Funchal: CEHA/SRTC, 143-175.

Vieira, Alberto (2018). Arquipélagos e ilhas entre memória, desmemória e identidade. Funchal: Cadernos de Divulgação do CEHA.

[1] Alberto Vieira conceived the idea of building a pantheon of regional heroes in the sense of differentiating between regional and national history: “desenvolvem-se os estudos locais e regionais. A História local e regional ganha evidência e diferencia-se da nacional. Constrói-se o panteão de heróis regionais” (Vieira, 2018: 20).

Orlanda Amarílis

Orlanda Amarílis Lopes Rodrigues Fernandes Ferreira was a Cape Verdean writer, born on the island of Santiago, on October 8, 1924. In Mindelo (island of São Vicente), she completed primary and secondary school, before moving to the Portuguese State of Goa, where he finished his studies for the Primary Teaching. In Lisbon, he graduated in Pedagogical Sciences at the Universidade de Lisboa. He died in the portuguese capital on February 1, 2014.

Literature and Linguistics were always a presence in her life, through her husband, the writer Manuel Ferreira (Leiria, 7-18-1917/Linda-a-Velha, 3-17-1992), a scholar of Lusophone African literature and cultures, author of No Reino de Caliban and A Aventura Crioula, through her father, Armando Napoleão Rodrigues Fernandes (Brava, 7-1-1889/Praia, 6-19-1969), who published the first Creole-Portuguese dictionary, O Dialecto Crioulo: Léxico do Dialecto Crioulo do Arquipélago de Cabo Verde, and through Baltazar Lopes da Silva (São Nicolau, 4-23-1907/Lisbon, 5-28-1989), author of Chiquinho and founder of the magazine Claridade.

Orlanda Amarílis, as a member of the Academia Cultivar, founded by students from the Liceu Gil Eanes, and a contributor to the magazine Certeza (1944), belonged to the Geração de Certeza, whose main aim is to discuss the isolation of the Cape Verde archipelago and the islands from each other, with the purpose of edifying Cape Verdean culture and identity: “os escritores da Geração de Certeza propõem fincar os pés na terra e assumem um compromisso com a ação e a mudança, a partir, sobretudo, de textos literários que privilegiem a reconstrução da identidade cabo-verdiana e o combate à opressão” (Deus, 2020: 75-76).

In relation to the Geração de Certeza and supposed problem with the claridosos, Orlanda Amarílis speaks of a work of continuity:

quando apareceu a Certeza, não foi para combater a Claridade como ouvi algures. Até já ouvi que Certeza não foi marco nenhum. No entanto, para nós [os membros da Academia Cultivar], Certeza viria trazer algo de novo. Havia um pulsar diferente dentro de nós, de uma geração posterior, portanto mais recente que os fundadores da Claridade. Fundar Certeza foi dar continuidade ao que a Claridade tinha iniciado. (Laban, 1992: 271-272)

Over time, Amarílis became one of the most important female faces in Cape Verdean literature, expressing, in her work, Cape Verdean women and the diaspora. Their stories reveal an important contribution to the registration and dissemination of Cape Verde’s intangible heritage.

Upon her return, after a long exile, she recalls her lost insularity, looking in that time of physical distance for the strength that made her write and publicize the life of the islands, even in the “tontice ingénua” (naive foolishness) of being able to relive that time:

eu fui colocada na posição de procura de um universo perdido e, se essa rotura existiu virtualmente, foi bom, porque me obrigou a escrever. No entanto, o meu clima emocional de então não tem razão de ser neste momento. É uma tontice ingénua pensarmos ser possível, ao fim de tantos anos de ausência, reviver as emoções de então. […]. Quando há alguns anos voltei a Cabo Verde, perante mim espalharam-se as cinzas do vulcão que foi a minha vida até aos dezasseis anos. (Laban, 1992: 263)

As the most outstanding work we consider Cais do Sodré té Salamansa (1974; 1991), whose title is a reference to Lisbon and the island of São Vicente, more precisely to the village located northeast of Mindelo. The set of seven short stories makes known the marks that we point out in Orlanda Amarílis’s stories, with relevance to the diaspora, the woman and the Cape Verdean feeling of abandonment and return to the islands, in a journey that started in “Cais do Sodré” and ended in “Salamansa”.

With characters that embody the islands, for their identity, for their language (expressions, forms of treatment, songs, everyday habits), for the difficulty and hardship of life, and for the subtlety dichotomous, physical and figurative, between the character that leaves the space of the archipelago and the one that remains, “estando em exílio, contrapõem a todo tempo a memória de sua identidade cabo-verdiana às modificações causadas pela distância espacial e temporal, e essa distância vai se inserindo nas suas filiações identitárias” (Silva, 2010: 63), Orlanda Amarílis offers a reflection on “questões importantes do cenário sociocultural cabo-verdiano como, por exemplo, a ressignificação da identidade cultural, a violência de gênero, a opressão sofrida pelas mulheres, a solidão, a emigração” (Deus, 2020: 80).

From Cais do Sodré to Salamansa, we highlight what we can consider a synthesis of the writing of Orlanda Amarílis. In the final part of the short story “Salamansa”, Antoninha “garganteia com sabura” (Amarílis, 1991: 82) a song in Creole, which is a motto to invoke the beach of Salamansa, communion with the sea and the emigrant Linda, a girl from “rua do Cavoquinho” (Amarílis, 1991: 80), who symbolizes the difficulties of the life of the women of the islands: “Oh, Salamansa, praia de ondas soltas e barulhentas como meninas intentadas em dia de S. João. Oh, Salamansa, de peixe frito nos pratos cobertos no fundo dos balaios e canecas de milho ilhado por titia em caldeiras com areia quente. Areia de Salamansa, Linda a rolar na areia” (Amarílis, 1991: 82).

Of the author’s works, we have to mention, in addition to Cais do Sodré té Salamansa, Ilhéu dos pássaros (1982), A casa dos Mastros (1989), Facécias e Peripécias (1990), A tartaruguinha (1997).

References

Amarílis, Orlanda (1991). Cais do Sodré té Salamansa. Linda-a-Velha: ALAC.

Deus, Lílian Paula Serra e (2020). Orlanda Amarílis, Vera Duarte e Dina Salústio: a tessitura da escrita de autoria feminina na ficção cabo-verdiana. In Regina Dalcastagnè (Dir.). Veredas – Revista da Associação Internacional de Lusitanistas, nº 33. Coimbra: Associação Internacional de Lusitanistas. 74-87.

Figueira, Paulo (2014).Estudo Lexical sobre Cais do Sodré Té Salamansa, de Orlanda Amarílis. In Marcelino de Castro (Dir.). Islenha, nº 55. Funchal: DRAC. 63-74.

Laban, Michel (1992). Cabo Verde: encontro com escritores. Vol. I. Porto: Fundação Engenheiro António de Almeida.

Laranjeira, Pires (1987). Formação e desenvolvimento das literaturas africanas de língua portuguesa. In Literaturas africanas de língua portuguesa. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 15-24.

Mariano, Gabriel (1991). Cultura caboverdeana – ensaios. Lisboa: Vega.

Silva, Elisa Maria Taborda da (2010). Cais do Sodré té Salamansa: o cabo-verdiano em exílio. In Beatriz Junqueira Guimarães (Ed.). Cadernos CESPUC de Pesquisa, nº 19. Belo Horizonte: Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais. 61-70.

Trigo, Salvato (1987). Literatura colonial/Literaturas africanas. In Literaturas africanas de língua portuguesa. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 139-158.

Art Islands

An Art Island refers to an island characterized by prominent artistic or creative elements such as contemporary art museums, artist studios, site-specific art events, communities of artists, and art festivals that are often created by famous artists, architects, and creators (Qu 2020; Prince, Qu, and Zollet 2021). Representative cases include peripheral islands Naoshima, Teshima, and Inujima in the Seto Inland Sea of Japan; Fogo Island Arts’ Bridge Studio on a remote island of Newfoundland, Canada, and the craft-art island of Bornholm, Sweden. Unlike the original island art, ‘art island’ implies a reterritorialization/creative place-making process (intervening in, interacting with, as well as influencing the co-creation between art and communities) shaped by art development in a context of social transformation. An important feature is social transformation: art islands frequently deploy socially engaged artwork and events. (Qu 2020; Crawshaw 2018; Favell 2016; Mccormick 2022).

Art intervenes on the island

Art Islands involve interrelated processes that co-create a new art island identity between art and destination. Socially engaged art brings site-specific and community based public artworks, art projects, or events into a community (Qu 2019; Mccormick 2022). It imports typically non-local artistic and cultural elements that impact the local community’s original landscape, lifestyle, art, and culture (ibid). The social practice transition of contemporary art consists of stepping out of art museums and the traditional art world into the urban and rural social context as relational art sites (Qu 2020). Relational art sites are “assemblages, they are hybrid spaces where the line between what is essentially rural and urban, as well as local and global, is blurred through their intensive interactions with extra-local people, ideas, materials, capital, investments, discourses, and processes” (Prince, Qu, and Zollet 2021, 250). The transition from original island community to art island is marked by concurrently changing processes of intervention, resistance, adaptation, and co-creation at the local level (ibid). Artists and arts organizers often contemplate the utopic ideals implied in “art islands” (Favell 2016). In short, the community level outcomes of art-island intervention are not limited to art but connect to rural/urban planning, art tourism, creative place-making, rural development and revitalization (Qu 2020; Prince, Qu, and Zollet 2021).

Art interacts with the island

Within communities, art is usually described as having the potential to “read” local issues rather than solve them. (Crawshaw and Gkartzios 2016). Art is limited in its capacity to remedy social issues (Qu 2020; 2019). Merely creating art museums and artworks or otherwise making an island more “artistic” does not necessarily make an art island. The overlapping relationships between art and tourism are becoming inseparable on art islands (Franklin 2018). Often, art islands mix art development with tourism development (Qu 2019; 2020), accompanied by creative entrepreneurship (Prince, Qu, and Zollet 2021; McCormick and Qu 2021).

Art can be also considered as “an ingredient of landscape planning” (Crawshaw 2018, 10). During the art tourism reterritorialization process, observing whether the development enhances community prosperity or rather brings a commercialized destruction to the community is essential to evaluate whether art is only ‘on’ or also ‘for’ an island (Qu 2020).

Art island co-creation

Aside from the external development of art or art tourism, the endogenous efforts within communities play an important role in creating art islands. Creative residents with businesses have the power to co-create the art island community through their resourceful behaviors by enhancing social, tourism, and art development (Mccormick and Qu 2021; Qu, McCormick, and Funck 2020). Newcomers also play an important role; urban-to-rural migrants, for example, “are more likely to establish fancy cafés and guesthouses, often incorporating elements of contemporary design in their operations to adhere to the ‘art island’ character.” (Prince, Qu, and Zollet 2021, 248). A healthy neo-endogenous synergy between art and island provides a relational understanding of this co-creation mechanism. Critically, given that each island possesses its own unique social structure and cultural context, no two art islands are alike. Each has its own set of interrelationships and its own brand of creativity. Art islands are complex, trans-local assemblages of contemporary art and tourism, shaped by complex art-community co-create and exchange.

Bibliography (Chicago Manual of Style)

Crawshaw, Julie. 2018. “Island Making: Planning Artistic Collaboration.” Landscape Research 43 (2): 211–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1291922.

Crawshaw, Julie, and Menelaos Gkartzios. 2016. “Getting to Know the Island: Artistic Experiments in Rural Community Development.” Journal of Rural Studies 43: 134–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.007.

Favell, Adrian. 2016. “Islands for Life: Artistic Responses to Remote Social Polarization and Population Decline in Japan.” In Sustainability in Contemporary Rural Japan: Challenges and Opportunities, edited by Stephanie Assmann, 109–24. London and New York: Routledge.

Franklin, Adrian. 2018. “Art Tourism: A New Field for Tourist Studies.” Tourist Studies 18 (4): 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797618815025.

McCormick, A. D. (2022). Augmenting Small-Island Heritage through Site-Specific Art: A View from Naoshima. Okinawan Journal of Island Studies 3 (1).

Mccormick, A D, and Meng Qu. 2021. “Community Resourcefulness Under Pandemic Pressure: A Japanese Island’s Creative Network.” Geographical Sciences (Chiri-Kagaku) 76 (2): 74–86.

Prince, Solène, Meng Qu, and Simona Zollet. 2021. “The Making of Art Islands: A Comparative Analysis of Translocal Assemblages of Contemporary Art and Tourism.” Island Studies Journal 16 (1): 235–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.175.

Qu, Meng. 2019. “Art Interventions on Japanese Islands: The Promise and Pitfalls of Artistic Interpretations of Community.” The International Journal of Social, Political and Community Agendas in the Arts 14 (3): 19–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18848/2326-9960/CGP/v14i03/19-38.

———. 2020. “Teshima – from Island Art to the Art Island.” Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures 14 (2): 250–65. https://doi.org/10.21463/shima.14.2.16.

Qu, Meng, A. D. McCormick, and Carolin Funck. 2020. “Community Resourcefulness and Partnerships in Rural Tourism.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1849233.

Island Vulnerability and Resilience

Vulnerability and resilience are nebulous and contested concepts. Island studies has provided plenty for understanding them, sorting out differences, and proposing ways forward. Two key points are (i) vulnerability and resilience are not opposites and (ii) they are processes, not states.

Vulnerability and resilience are social constructions. Many languages do not have direct translations for the words and many cultures do not have the notions, especially as defined and debated in academia. As such, both must be explained in detail to be communicated and acted on. Island studies contributes significantly by noting that both exist simultaneously, meshing with each other, and that both must arise by people and societies interacting with themselves and their environments. They are also much more than interaction, since nature and culture cannot be separated, as is the case for society and the environment. Thus, vulnerability and resilience are simply part of being, rather than distinct entities or traits.

As such, they express and espouse reasons for ending up with situations and circumstances where dealing with opportunity and adversity is more possible or less possible. They are long-term processes describing why observed states exist, not merely descriptions of those states. These explanations must cover society and the environment interlacing rather than disconnecting from one another and must involve histories and potential futures, not merely snapshots in space and time.

For islands, environmental phenomena and changes are frequently seen as exposing or creating vulnerabilities and resiliences. Yet an earthquake or the changing climate do not tell people and societies how to respond. Instead, those with power, opportunities, and resources make decisions about long-term governance aspects including equality, equity, collective support, and societal services.

We know how to construct infrastructure to withstand earthquakes. This task cannot happen overnight, but requires building codes, planning regulations, skilled professions, and choices in order to succeed. Taking island examples, leaders inside and outside Haiti controlling the country over decades decided not to build for earthquakes, leading to devastating disasters in 2010 and 2021. Meanwhile, Japan adopted a different approach meaning that few collapses were witnessed despite earthquakes in 2003, 2011 (which had a terrible tsunami toll), and 2022 that were far stronger than Haiti’s.

This long-term process of stopping or permitting earthquake-related damage is a societal choice, meaning that disasters emerge from the choice of vulnerability and resilience processes. Disasters do not come from earthquakes or other environmental phenomena, so they are not from nature and “natural disaster” is a misnomer.

Since climate change affects the weather and weather does not cause disasters, climate change does not often affect disasters. For instance, islands have experienced tropical cyclones for millennia, with the storm season happening annually. Plenty of knowledge exists to avoid damage and plenty of time has existed to implement this knowledge, yet disasters are still witnessed frequently such as Hurricane Maria in the Caribbean in 2017 and Cyclone Harold in the Pacific in 2020. When people and infrastructure are not ready for a storm, then disasters occur. Climate change increases intensity and decreases frequency of tropical cyclones, yet does not impact long-term human choices to prepare (creating resilience) or not (creating vulnerability). The choice not to do so is a crisis of human choice, not a “climate crisis” or “climate emergency”—so those phrases are also misnomers.

Island studies has long taught the islander mantra that environmental and social changes are always to be expected at all time and space scales. Vulnerability becomes the social process of expecting life to be constant and not being ready to deal with different or altering environments, at short (e.g. earthquake) or long (e.g. climate change) time scales. Vulnerabilities most commonly arise because people do not have the options, power, or resources to change their situation due to factors such as poverty, oppression, and marginalisation. Others make the decision for the majority to be vulnerable. Resilience becomes the process of continual adjustment and flexibility to make the most of what the ever-shifting environment and society can offer to support everyone’s life and livelihoods. To do so requires options, power, and resources.

Yet island studies demonstrates that limits to resilience are nonetheless evident. Human history displays a long list of island communities being wiped out and entire islands being forcibly abandoned. Manam Island, Papua New Guinea has been evacuated a few times due to volcanic eruptions. Many Pacific island communities disappeared in the fourteenth century due to a major regional climatic and sea-level change while nuclear testing during the Cold War left many atolls uninhabitable. The Beothuk indigenous people of Newfoundland died out due to violent and disease-ridden colonialism. In the 1960s and 1970s, Chagossians were forced off their Indian Ocean archipelago to make way for a military base. All such situations test resilience—or lose it entirely.

Island studies thus demonstrates the construction of vulnerability and resilience as concepts, as processes, and as realities, illustrating the care in interpretation and application needed for both in order to capture a comprehensive picture. Vulnerability and resilience neither contradict nor oppose each other, rather overlapping and morphing according to context and nuance. Island vulnerability and resilience are very much based on the perspectives of those observing and affected.

Cenáculo

Cenáculo was a group of gatherings that met at the Golden Gate[1], founded by João dos Reis Gomes, Fr. Fernando Augusto da Silva and Alberto Artur Sarmento, which became relevant for the ideas presented, although, so far, no minutes or official documents of the gathering that allow us to objectively evaluate the intellectual debate. As for the constituent members, and aware of the lack of space for the acceptance of new elements, Joana Góis reports on 24 members (Góis, 2015: 24-25), among them the son of João dos Reis Gomes, Álvaro Reis Gomes.

Visconde do Porto da Cruz expresses that the group is not open to new generations: “Em volta do ‘Cenáculo’ apareciam curiosos que não se afoitavam a aproximar-se de centro tão restrito, onde, especialmente, Reis Gomes e o Padre Fernando da Silva, não viam com bons olhos o advento de novos valores” (Porto da Cruz, 1953: 12).

Joana Góis shares Visconde’s opinion and adds that the gathering was a mystery in terms of collective action, but expressed itself very well through the role of its individualities: “A ‘misteriosa’ geração reunia-se em silêncio e permaneceu, acima de tudo, na esfera privada e sem expressão pública dos seus trabalhos” (Góis, 2015: 21).

Cenáculo elements gravitate towards the edition of two periodicals directed by Major João dos Reis Gomes, Heraldo da Madeira and Diário da Madeira, respectively, whose orientations approach subjects related to autonomy, regionalism and history, literature, traditions and politics related to Madeira, all under the inspiration of a certain conservatism and patriotism, but with the focus on the construction and defense of a Madeiran identity.

We believe that the most outstanding action of Cenáculo, as a collective, is the formation of Mesa do Centenário, with the objective of carrying out the celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Madeira. Always with the intention of a nationwide celebration, the action of the members of Mesa do Centenário led to the challenge of modernizing Funchal, in order to dignify the event’s stage.

Between Cenáculo and Mesa do Centenário there seems to have been a natural transition and, based on the positions conceived and publicized in the Diário da Madeira, the commemorative program of the Madeira Centenary was designed. The “Geração do Cenáculo” managed to add a cultural foundation to the event, which triggered an atmosphere of conflict with metropolis, which meant that, between December 1922 and January 1923, Lisbon was not represented, despite the several international commissions.

The fact turned out to be fruitless due to the lack of argumentative sustainability in relation to the Madeiran identity because, according to Nelson Veríssimo, “Faltaram intelectuais que exaltassem esses princípios que congregaram vontades e animaram a condução de populações por entusiásticos guias” (Veríssimo, 1985: 232). After the festivities, the “cenaculistas” were also participatory voices in the Comissão de Estudo para as Bases da Autonomia da Madeira.

Cenáculo’s line of thought approaches, from what we can assess from its members, through the newspapers and the action of Mesa do Centenario, a Madeiran identity close to patriotic values (Portuguese settlement, exaltation of the Portuguese element) and not so much cosmopolitanism also present in the Madeiran feeling[2].

The meetings and ideas of the “ninho da águia” (Eagle’s Nest) are the target of critics who were fascinated by the group: “[Reis Gomes] Vindo do labirinto da vista da cidade, depois de haver feito a sua longa jornada profissional diária – […] – encontrava no íntimo cavaco com amigos, reunidos numa das salas do hotel Golden Gate, o benéfico oásis para o seu descanso físico e intelectual” (Vieira, 1950: 18). In relation to literature, João dos Reis Gomes and the “Geração do Cenáculo” became forerunners of intellectuals who, in the 1940s, saw “na narrativa de ficção com forte cunho regionalista” the possibility “de constituir uma história, uma memória, uma biblioteca, uma identidade cultural forte para as gerações futuras da Ilha” (Santos, 2008: 569).

References

Góis, Joana Catarina Silva (2015). A Geração do Cenáculo e as Tertúlias Intelectuais Madeirenses (da I República aos anos 1940) [Masters dissertation]. Porto: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto.

Gouveia, Horácio Bento de (1952). Reis Gomes – Homem de Letras. In Das Artes e Da História da Madeira, nº 13. Funchal, 29-31.

Gouveia, Horácio Bento de (1969). O académico e escritor João dos Reis Gomes. In Panorama, nº 29. Lisboa, 6-9.

Figueira, Paulo (2021). João dos Reis Gomes: contributo literário para a divulgação da História da Madeira [Phd thesis]. Funchal: Universidade da Madeira.

Pestana, César (1952). Academias e tertúlias literárias da Madeira – “O Cenáculo”. In Das Artes e da História da Madeira, vol. II, nº 38. Funchal, 21-23.

Porto da Cruz, Visconde (1953). Notas & Comentários Para a História Literária da Madeira, 3º Período: 1910-1952, vol. III. Funchal: Câmara Municipal do Funchal.

Salgueiro, Ana (2011). Os imaginários culturais na construção identitária madeirense (implicações cultura/economia/relações de poder). In Anuário do Centro Estudos e História do Atlântico, nº 3. Funchal: CEHA, 184-204.

Santos, Thierry Proença dos (2008). Gerações, antologias e outras afinidades literárias: a construção de uma identidade cultural na Madeira. In Dedalus, nº 11-12. Lisboa: APLC/Cosmos, 559-582.

Veríssimo, Nelson (1985). Em 1917 a Madeira reclama Autonomia. In António Loja (dir.). Atlântico, nº 3. Funchal: Eurolitho, 230-233.

Vieira, G. Brazão (1950). Um grande vulto que a morte levou: João dos Reis Gomes. In Das Artes e da História da Madeira, nº 2. Funchal, 17-19.

[1] The Golden Gate, known as one of the “esquinas do mundo”, in the words of Ferreira de Castro, and due to its geographical location, close to the Cathedral of Funchal, the port, the Palácio de São Lourenço and the Statue of Zarco, is a famous restaurant space that favors the passage of citizens from all over the world, mainly through its esplanade, something that is still verifiable today.

[2] Cf. Ana Salgueiro, “Os imaginários culturais na construção identitária madeirense (implicações cultura/economia/relações de poder)”, 184-204.

Islandness

At present, there are two prevailing views of what islandness is, and which is the difference between this term and its relative term, insularity. The first perspective adopts the narrative that islandness is somewhat an academic evolution of insularity and the second suggests that insularity is a standard feature like small size, remoteness and isolation, special experiential identity and rich and vulnerable natural and cultural environment. Adding to the public discussion that relates to how sciences view islands and consequently how islands are managed through public policies, it is crucial to shed light to islandness as a contemporary term.

As Conkling (2007, 200) argues, islands are most fundamentally defined by the presence of often frightening and occasionally impassable bodies of water that create a sense of a place closer to the natural world and to neighbors whose eccentricities are tolerated and embraced. Given this affirmation, he argues (Conkling 2007, 200) that “islandness is often considered as a metaphysical sensation deriving from the heightened experiences that accompany the physical isolation of island life, […] as an important metacultural phenomenon that helps maintain island communities in spite of daunting economic pressures to abandon them”. He briefly describes islandness as “a construct of the mind, a singular way of looking at the world”. It is either being on an island or not.

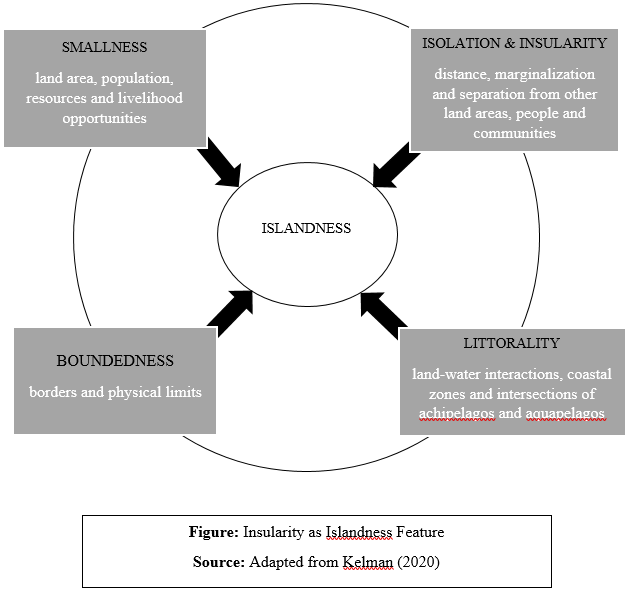

In any case, given that both concepts (insularity and islandness) communicate, islandness is also assumed to include four main characteristics/aspects: boundedness, smallness, isolation and littorality (Kelman 2020, 6). Boundedness describes the borders and the physical limits of islands. Smallness refers to land area, population, resources and livelihood opportunities. Isolation stands for distance, marginalization and separation from other land areas, people and communities. Last but not least, littorality, refers to land-water interactions, coastal zones and intersections of achipelagos and aquapelagos (Kelman 2020, 7).

Additionally, Baldacchino (2004, 278) from another more practical perspective, argues that “islandness is an intervening variable that does not determine, but contours and conditions social and physical events in distinct, and distinctly relevant, ways”. He underlines that “this is no weakness or deficiency; rather, therein lies the field’s major strength and enormous potential” (Baldacchino 2006, 9). He also makes an interesting suggestion about the link between islandness and insularity: “researchers and practitioners should be aware of how deep-rooted and stultifying the social consequences of islandness can be and this specific feature can actually be called insularity” Baldacchino (2008, 49). So, he assumes that islandness is not a synonymous of insularity, but the latter is one of many features of islandness that describes a specific condition that characterizes island communities. Insularity can be regarded as a brief term to describe insular remoteness which can include three types of remoteness: the physical, the imaginative and the politico legal (Nicolini and Perrin 2020).

There is sufficient evidence that islands – small islands in particular – are distinct enough sites, or harbour extreme enough renditions of more general processes, to warrant their continued respect as subjects/objects of academic focus and inquiry. There is a debate within the nissology framework, i.e. the study of islands in their own terms, about the uniqueness of islands. Still others find islands ‘living labs’, central to understanding what happens subsequently on mainland territory. Islands are often viewed as places that need to be saved and treated differently from the mainland to reach dominant continental standards. Indeed, islands have always been a bone of contention, either seen as paradise or hell.

Cross-disciplinary research on the essence of islands and what constitutes the insular condition within a growing framework of “nissology”, has reinforced the need to distinct insularity from islandness. No island is insular, meaning “entire to itself”. An approach that is based on the argument that islands need to be studied on their own terms which is also aligned with a more politically correct usage of relative terminology, has gradually substituted insularity with islandness. Insularity as a term, has been extensively used in academia and public speaking to describe expresses ‘objective’ and measurable characteristics, including small areal size, small population (small market), limited resources, isolation, and remoteness, as well as unique natural and cultural environments, that synthesize an insular condition. However, it also involves a distinctive ‘experiential identity’, which is a non-measurable quality expressing the various symbols that islands are connected to (Spilanis et al. 2011, 9). The term “insularity” has unwittingly come along with a sematic baggage of separation and backwardness. This negativism does not mete out fair justice to the subject matter (Baldacchino 2004,272).

And it is of great importance that islandness and all four dimensions mentioned above, needs to be more closely examined trough various discipline lenses. The core of “island studies” is the constitution of “islandness” and its possible or plausible influence by the traditional subject uni-disciplines (such as archaeology, economics or literature), subject multi-disciplines (such as political economy or biogeography) or policy foci/issues (such as governance, social capital, waste disposal, language extinction or sustainable tourism) (Baldacchino 2006, 9). The evolution in terminology that relates to islands is only one of the signs that affirms that islands are indeed loci for major issues and developments in the 21st century, which their being studied in their own terms considered to be one of the most fundamental epistemic challenges today.

Mitropoulou Angeliki & Spilanis Ioannis

References

Baldacchino, G. 2004. The coming of age of island studies. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 95(3) : 272-283.

—. 2006. Islands, island studies, island studies journal. Island Studies Journal, 1(1): 3-18.

—. 2008. Studying islands: on whose terms? Some epistemological and methodological challenges to the pursuit of island studies. Island Studies Journal, 3(1): 37-56.

Conkling, P. 2007. On islanders and islandness. Geographical Review, 97(2): 191-201.

Kelman, I. 2020. Islands of vulnerability and resilience: Manufactured stereotypes?. Area, 52(1): 6-13.

Nicolini, M., & Perrin, T. 2020. Geographical Connections: Law, Islands, and Remoteness. Liverpool Law Review, 1-14.

Spilanis, I., Kizos, T., Biggi, M., Vaitis, M., Kokkoris, G. et al. (2011). The Development of the Islands – European Islands and Cohesion Policy (EUROISLANDS). Final report. Luxemburg: ESPON & University of the Aegean. Available at: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/inception_report_full_version.pdf (Accessed: 07 December 2020)