At present, there are two prevailing views of what islandness is, and which is the difference between this term and its relative term, insularity. The first perspective adopts the narrative that islandness is somewhat an academic evolution of insularity and the second suggests that insularity is a standard feature like small size, remoteness and isolation, special experiential identity and rich and vulnerable natural and cultural environment. Adding to the public discussion that relates to how sciences view islands and consequently how islands are managed through public policies, it is crucial to shed light to islandness as a contemporary term.

As Conkling (2007, 200) argues, islands are most fundamentally defined by the presence of often frightening and occasionally impassable bodies of water that create a sense of a place closer to the natural world and to neighbors whose eccentricities are tolerated and embraced. Given this affirmation, he argues (Conkling 2007, 200) that “islandness is often considered as a metaphysical sensation deriving from the heightened experiences that accompany the physical isolation of island life, […] as an important metacultural phenomenon that helps maintain island communities in spite of daunting economic pressures to abandon them”. He briefly describes islandness as “a construct of the mind, a singular way of looking at the world”. It is either being on an island or not.

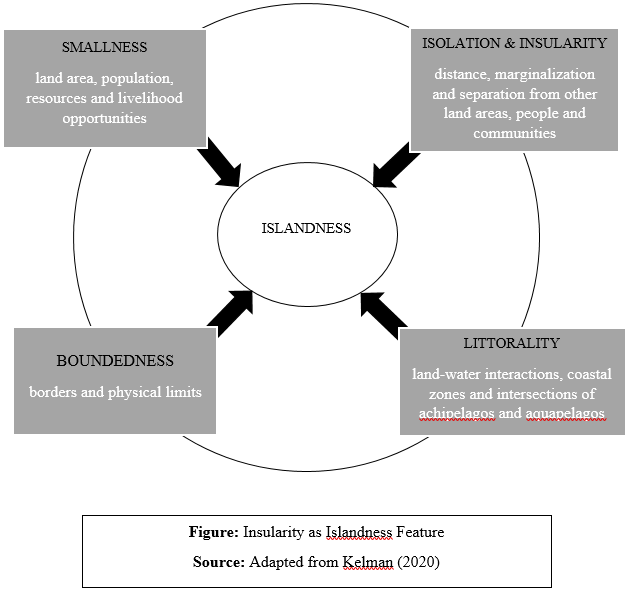

In any case, given that both concepts (insularity and islandness) communicate, islandness is also assumed to include four main characteristics/aspects: boundedness, smallness, isolation and littorality (Kelman 2020, 6). Boundedness describes the borders and the physical limits of islands. Smallness refers to land area, population, resources and livelihood opportunities. Isolation stands for distance, marginalization and separation from other land areas, people and communities. Last but not least, littorality, refers to land-water interactions, coastal zones and intersections of achipelagos and aquapelagos (Kelman 2020, 7).

Additionally, Baldacchino (2004, 278) from another more practical perspective, argues that “islandness is an intervening variable that does not determine, but contours and conditions social and physical events in distinct, and distinctly relevant, ways”. He underlines that “this is no weakness or deficiency; rather, therein lies the field’s major strength and enormous potential” (Baldacchino 2006, 9). He also makes an interesting suggestion about the link between islandness and insularity: “researchers and practitioners should be aware of how deep-rooted and stultifying the social consequences of islandness can be and this specific feature can actually be called insularity” Baldacchino (2008, 49). So, he assumes that islandness is not a synonymous of insularity, but the latter is one of many features of islandness that describes a specific condition that characterizes island communities. Insularity can be regarded as a brief term to describe insular remoteness which can include three types of remoteness: the physical, the imaginative and the politico legal (Nicolini and Perrin 2020).

There is sufficient evidence that islands – small islands in particular – are distinct enough sites, or harbour extreme enough renditions of more general processes, to warrant their continued respect as subjects/objects of academic focus and inquiry. There is a debate within the nissology framework, i.e. the study of islands in their own terms, about the uniqueness of islands. Still others find islands ‘living labs’, central to understanding what happens subsequently on mainland territory. Islands are often viewed as places that need to be saved and treated differently from the mainland to reach dominant continental standards. Indeed, islands have always been a bone of contention, either seen as paradise or hell.

Cross-disciplinary research on the essence of islands and what constitutes the insular condition within a growing framework of “nissology”, has reinforced the need to distinct insularity from islandness. No island is insular, meaning “entire to itself”. An approach that is based on the argument that islands need to be studied on their own terms which is also aligned with a more politically correct usage of relative terminology, has gradually substituted insularity with islandness. Insularity as a term, has been extensively used in academia and public speaking to describe expresses ‘objective’ and measurable characteristics, including small areal size, small population (small market), limited resources, isolation, and remoteness, as well as unique natural and cultural environments, that synthesize an insular condition. However, it also involves a distinctive ‘experiential identity’, which is a non-measurable quality expressing the various symbols that islands are connected to (Spilanis et al. 2011, 9). The term “insularity” has unwittingly come along with a sematic baggage of separation and backwardness. This negativism does not mete out fair justice to the subject matter (Baldacchino 2004,272).

And it is of great importance that islandness and all four dimensions mentioned above, needs to be more closely examined trough various discipline lenses. The core of “island studies” is the constitution of “islandness” and its possible or plausible influence by the traditional subject uni-disciplines (such as archaeology, economics or literature), subject multi-disciplines (such as political economy or biogeography) or policy foci/issues (such as governance, social capital, waste disposal, language extinction or sustainable tourism) (Baldacchino 2006, 9). The evolution in terminology that relates to islands is only one of the signs that affirms that islands are indeed loci for major issues and developments in the 21st century, which their being studied in their own terms considered to be one of the most fundamental epistemic challenges today.

Mitropoulou Angeliki & Spilanis Ioannis

References

Baldacchino, G. 2004. The coming of age of island studies. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 95(3) : 272-283.

—. 2006. Islands, island studies, island studies journal. Island Studies Journal, 1(1): 3-18.

—. 2008. Studying islands: on whose terms? Some epistemological and methodological challenges to the pursuit of island studies. Island Studies Journal, 3(1): 37-56.

Conkling, P. 2007. On islanders and islandness. Geographical Review, 97(2): 191-201.

Kelman, I. 2020. Islands of vulnerability and resilience: Manufactured stereotypes?. Area, 52(1): 6-13.

Nicolini, M., & Perrin, T. 2020. Geographical Connections: Law, Islands, and Remoteness. Liverpool Law Review, 1-14.

Spilanis, I., Kizos, T., Biggi, M., Vaitis, M., Kokkoris, G. et al. (2011). The Development of the Islands – European Islands and Cohesion Policy (EUROISLANDS). Final report. Luxemburg: ESPON & University of the Aegean. Available at: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/inception_report_full_version.pdf (Accessed: 07 December 2020)