“The world is full of islands” (Baldacchino, 2006, p.4). It is not surprising that, over the last decades, there has been an increased interest in island studies, attracting researchers from different disciplinary areas who, together, have been able to promote this “new” line of research, thus developing the so-called “island science”.

Island science, although young, has shown great relevance in international studies, as demonstrated by the editorial title of the journal Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie: “The coming of Age of island studies” (Baldacchino, 2004), thus proclaiming the “maturity” of island studies (King, 2010).

For Young, the island is a place of secrecy and mystery, but its isolation also conditions its historical evolution (Young, 1999, p. 2). In this sense, the insular specificity may be in correlation with the hydraulic issue? This entry intends, therefore, to make known the main trends of Hydraulics at the research level. In this sense, and with regard to island territories, the article by Paulo Espinosa and Fernanda Cravidão, in “Revista Sociedade & Natureza”, entitled “A Ciência das Ilhas e os Estudos Insulares: Breves reflexões sobre o contributo da Geografia / The Science of Islands and the Insular Studies: brief point of view about the importance of geography”, contains a set of themes to be studied and reflected upon.

All emersed lands, of greater or lesser size, are surrounded by oceans, so islands inevitably occupy an extremely important place in world life (Biagini; Hoyle, 1999, p. 1). There are facts that translate, in a synthetic way, the real value of islands worldwide, although they are often ignored by most researchers. According to Baldacchino (2007), nearly 10% of the world population, almost 600 million people, currently live on islands, occupying about 7% of the Earth’s surface. Approximately a quarter of the world’s independent states are islands or archipelagos. Furthermore, islands assume themselves as differentiated identities and spaces in an increasingly homogeneous world, as a result of the globalisation process.

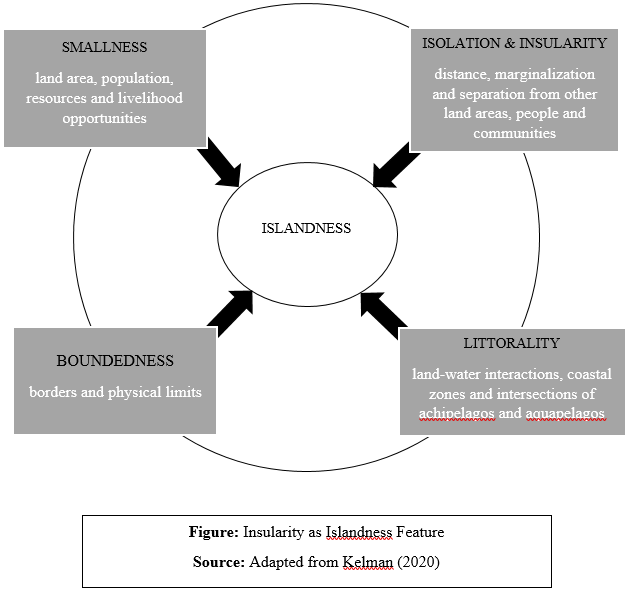

Despite their value, small island spaces are often associated with a set of structural constraints since “as a consequence of their scale, small islands are limited in size, land area, resources, economic and population potential, and political power” (Royle, 2001, p. 42). Thus, it is not surprising that of the total number of sovereign countries that are not entirely insular, only two have their capital on an island, these being Denmark and Equatorial Guinea, reflecting a political and functional preference for continental areas to the detriment of territories exclusively surrounded by water.

Thus, there are many difficulties and potentialities that we can find in the islands. For this reason, these spaces are extremely rich in terms of scientific study. Lockard & Drakakis-Smith (1997) state that the themes of islands that have most attracted the attention of researchers include, apart from tourist activity, emigration and return migration, transport and accessibility, limited resources such as water, and economic development policies.

Therefore, water has always been an essential factor in establishing life, in general, and mankind in particular. The importance of this liquid has led to an evolution in the techniques of transport for human consumption over the millennia (Baptista, 2011).

Despite this evolution, verified throughout the years of existence of the human race, it was in more recent history, mainly in the 20th century, that major advances in water supply systems were verified, due to the need to respond to the population increase verified around the globe and the emergence of new materials, such as, for example, polymers. Also at the design level, a major evolution was noted due to the discovery of new hydraulic laws, which allow optimizing the supply conditions (Baptista, 2011).

In most current cases, buildings are supplied through a public network that carries drinking water. However, there are situations in which the water is supplied from wells. In these cases, it is necessary to proceed in order to guarantee the potability of the water (Baptista, 2011).

In the execution of this type of project, essential factors are taken into account, such as economy, the conditions of application and use, the routing requirements and also the chemical constitution of each material, always bearing in mind the legislation governing this type of system. It is based on the optimization of these factors that water supply networks are built (APA, 2018).

Water planning aims to ground and guide the protection and management of waters and the compatibility of their uses with their availability in order to (APA, 2018):

- Guarantee their sustainable use, ensuring that the needs of current generations are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs;

- Provide criteria for allocation to the various types of intended uses, taking into account the economic value of each one, as well as to ensure the harmonisation of water management with regional development and sectoral policies, individual rights and local interests;

- Set environmental quality standards and criteria for water status.

From what has been described, I can say that there is no shortage of reasons to study this issue in an island context. Regardless of the perspective used, research on islands reveals a great thematic amplitude, since they can be analysed from different angles, and the discipline of Hydraulics can contribute to the study of “island sciences”, particularly with regard to hydraulic planning.

References

APA. (2018). Políticas, Água, Planeamento. Obtido de Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente: https://www.apambiente.pt/index.php?ref=16&subref=7&sub2ref=9#

Baptista, F. P. (2011). Sistemas Prediais de Distribuição de Água Fria. Lisboa: IST. Obtido de https://fenix.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/downloadFile/395142730852/Tese.pdf

Baldacchino, G. (2004). The Coming of Age of Island Studies. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geographie. V. 95, n. 3, pp. 272-283. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2004.00307.x

Baldacchino, G. (2006). Extreme Tourism: Lessons from the world cold water. Oxford: Elsevier, p. 4.

Baldacchino, G. (2007). Introducing a world of islands. In: Baldacchino, G. (Ed.). A World of Islands. Charlottetown: University of Prince Edward Island, Institute of Island Studies, p. 1-29.

Biagini, E. & Hoyle, B. (1999). Insularity and Development on an Oceanic Planet. In: Biagini, E. & Hoyle, B. (Eds.). Insularity and Development: international perspectives on islands. London: Pinter, p. 1.

King, R. (2010). A geografia, as ilhas e as migrações numa era de mobilidade global. In: Fosnseca, M. L. (Ed). Actas da Conferência Internacional – Aproximando Mundos Emigração e Imigração em Espaços Insulares. Lisboa: Fundação Luso-Americana para o Desenvolvimento, p. 27-62.

Lockhart, D. & Drakakis-Smith, D. (1997). Island Tourism: Trends and Perspectives. London: Mansell, 320 p.

Royle, S. (2001). A Geography of Islands: Small Island Insularity. London: Routledge, p. 42.

Young, L. B. (1999). Islands: Portraits of Miniature Worlds. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, p. 2.